Fantasy and horror author Steve Hugh Westenra makes a point on how body horror and queerness are strongly linked, and discusses the unsettling ever-changing nature of bodies, especially trans bodies.

CW: allusions to homophobia, transphobia, racism, antisemitism, ableism.

Body horror is a queer space.

Nowadays, in a popular sense in the West, queerness has come to denote primarily an identity (or a set of identities). To be queer is to have pronouns in your bio, to dress in the colours of a flag that communicates affiliation (and occasionally imparts it), to shop at particular stores, and to desire (or not desire) specific kinds of bodies. Queerness in this way can be exclusive: protecting and shepherding, while also policing whose queerness is the “right” kind, and whose voice gets to count in a show of hands (spoiler: it’s usually the white able-bodied ones).

But queerness has also always meant that which deviates from a prescribed or assumed norm. It’s that which veers away from Robert Frost’s path most travelled and twists or morphs when we attempt hold onto it too long and too tightly. Queerness, from this ever-peculiar angle, is by nature the devil’s “left.”1

If queerness is defined as that which is askew, aslant, asunder, then horror that focuses primarily on the body is the queerest of them all.

If queerness is defined as that which is askew, aslant, asunder, then of all the myriad subgenres under the Babadook’s umbrella, horror that focuses primarily on the body—and specifically the body’s permeability and its malleability—is the queerest of them all. It is here where the body under siege is not merely cut to (and from) in the blink of a teasing camera lens but lingered over. Lovingly. Longingly.

Body horror is a kind of pornography.

In body horror, the body is not only rendered vulnerable—the body is rendered. The before is just as essential as the after.

David Cronenberg’s The Fly knows this well, framing its hero—the scientist Seth Brundle [Jeff Goldblum]—in explicitly sexual terms.

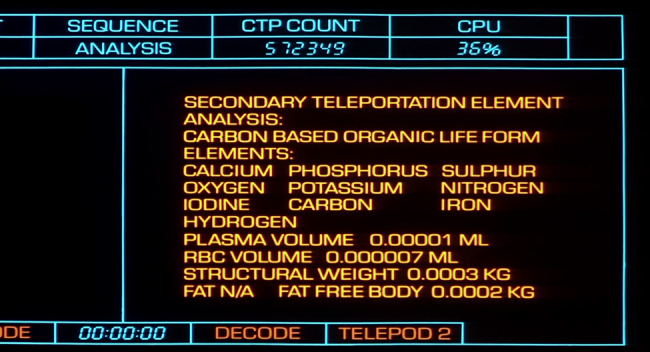

For those who haven’t seen Cronenberg’s remake of this fifties horror flick, The Fly follows Brundle’s attempts to invent a machine that will safely transport an object or person from one place to another in the blink of a compound eye. Brundle’s teleportational dreams are coupled with nervous longing for companionship. In this vein, the plot focuses as much on the love story between Brundle and Geena Davis’s Ronnie Quaife—a journalist reporting on Brundle’s discovery—as it does on the love story between the creator and his invention. Unfortunately for Brundle and Quaife, this is a Cronenberg film, not a Hallmark movie (HEA not included). When Brundle unknowingly enters the teleportation pod alongside a fly, the DNA of the two organisms is merged. At first, Brundle experiences his transformation as positive: his anxiety is replaced with a baffling confidence, and an increased libido ensures that (at least at first) he gets the girl. But Brundle’s drink from the well of a million self-help gurus has its drawbacks. Quaife is gradually put off by the swaggering machismo that has replaced Brundle’s eccentric magnetism, and even more put off when the Brundle that launched a thousand memes [see above: left] starts sprouting coarse hairs and developing the world’s worst case of acne.2

I choose The Fly as my example here for a number of reasons. 1) Its depiction of a beautiful body in decay cannot be uncoupled from the date of the film’s release—a time when audiences would have recognized in Brundle’s pock-marked skin and wasting form the spectre of HIV/AIDS, 2) Both through this linkage, as well as the film’s participation in a tradition of representing the anxious and effeminate Jewish (or Jewish-coded) male body as at once aberrant and desirable, the movie puts both a longing for the archetypal Other and the notion of a ruinous sexuality at its centre, 3) David Cronenberg is arguably the name most synonymous with body horror, and 4) On a purely selfish level, The Fly has always spoken to me as a queer text (which is a fancy way of saying I really like it).

There’s a lot I could say here about the politics of The Fly and its larger themes of Otherness in relation to the status quo, but the focus of this article is the body and to the body I shall return.

“Body horror pulls that which is inside us—that which ought not to be seen.”

In The Fly, as much as in Cronenberg’s other work (e.g. The Brood [1979], Dead Ringers [1988], and the highly underrated eXistenZ [1999]), the horror of the body is the horror inherent in bodies. These movies are less about anything totally alien to us (which would arguably be impossible to render on page or screen, as the thesis of cosmic horror stipulates), but about the alien within the self. Body horror pulls that which is inside us—that which ought not to be seen—outside into the world where it can be not only seen, but viscerally reckoned with. Parts of ourselves that are essential to our daily functioning, but whose recognition elicits panic and shock (after all, how many of us know what a spleen looks like), become not only a source of fear, but the very plot of the movie, or book, or game.

Body horror is squelch and viscosity and melt. It is dissolution and adherence and spread. It is the threat of limitless expansion as in Slither (2006) and the uncanny fear of one’s wasting flesh portrayed in Stephen King’s novel Thinner (1984) or any number of zombie films in which the rotting, emaciated, or bloated corpse stalks the living as a literal reminder of our mortality. Body horror reveals that that which we consider to be the self (the face, the skin, or our secondary sexual characteristics) is both ultimately and desperately fragile, and temporary.

“It’s the itch in the back of the mind that something’s not quite right about Cats (2019)”

As the fly, Brundle embodies what philosopher Julia Kristeva describes as the abject. I’ve often explained the abject with reference to feeling rather than fact. Both the uncanny and abject—what I would call the twin apparatuses used to generate horror in the audience—are known by the affective response they produce. The uncanny—put simply, a recognition of the familiar within the unfamiliar, as in the case of the cyborg or the corpse—produces the frisson, or the shudder. It’s the chill we feel reading a Gothic novel, or the itch in the back of the mind that something’s not quite right about Cats (2019) but we just can’t place what that thing is.3

If the uncanny is the shudder, the abject is the gag reflex. We experience revulsion at the sight of bodily fluids, or decaying matter, or, as Kristeva herself suggests, the thought of a skin forming on the surface of a glass of milk.4 The abject is also about desire—a pull towards that which we wish to disavow as being part of us. Horror, therefore, comes from our inability to totally deny that the grotesque form on screen or page represents something not only close to us, but integral to us.

Certain kinds of bodies are more liable than others to provoke horror and a sense of the abject. Cis women’s bodies and pregnant bodies are a focus of Kristeva’s (as well as Cronenberg’s), but we might add to these a fear and a pull toward any body that wears its gender (or lack thereof) on its skin. Trans bodies, racialized bodies, disabled bodies, and fat or “too thin” bodies exemplify the state of abjection from a normate perspective,5 and thus tend to be the blueprint for monstrous forms of all stripes. A sense of the abject (remember, a kind of “pull” alongside the gag reflex), is arguably the motivating force behind fascination with trans genitalia and unsolicited questions about what’s in someone’s pants. At the heart of the query is a kind of Schrödinger’s penis. Is it more horrific (read, desirable) for the answer to be one of presence or of lack? Perhaps, the answer isn’t one or the other, but the spectre of an answer. Not knowing is what keeps one on the edge of one’s seat. In body horror, however, the monster (and its genitals) is seen. The trick tends to be that, whatever shape the answer takes, it somehow still retains a level of ambiguity.

Body horror, in Cronenberg and elsewhere, tends to elide gender and sexual difference. Many of his films (The Brood, Shivers) deal with procreation in one form or another, and typically with an eye to asexual reproduction, reproduction through atypical means, and/or the impregnation of cis male bodies. The Fly engages with this theme through Brundle’s obsession with procreation—an obsession that is linked with a supposed primal drive that is awakened through the merging of human and non-human animal DNA. Here, the sex drive is rendered monstrous, the procreative urge the source of possible infection (the sanctity and security of Quaife’s body is suddenly put at risk). We worry as the viewers for what impregnation with Brundle’s child could mean for Quaife on a physical level, but also about the child that may result from such a union. This worry is not so different (that is, not different at all) from concerns about either miscegenation or the spread of deadly contagion such as HIV.

“In body horror, the objectification of the bodies on screen is deliberate and sought after.”

To circle back, body horror is an inherently sexualized medium, and one in which the camera and storyline(s) linger over the abject, often ruined, body. The body at an angle. The body askew. Here, the acts of not just looking, but staring, lingering, admiring, and cringing are encouraged. When I say that body horror is pornography, therefore, I’m alluding to the ways that in body horror, the objectification of the bodies on screen is deliberate and sought after. There’s also a hunger, it seems to me, in the way fans express their eagerness to witness the gross, the disturbing, the subversive, and the perverse. I mentioned earlier that the before is as important in body horror as the after. This is to say that a body in a state of flux (whether disintegration, expansion, or mutation into another type of organism), is of more interest to the subgenre than an already monstrous being that is self-contained and in no danger of rupture or mutation (for example, consider a giant animal such as an alligator, shark, or even King Kong). The question of what is it? hovers over normate reactions to real-life non-normative bodies in the same way that it hangs over the monstrous hybrid body of Brundlefly: audiences are repulsed but also compelled. Audiences are curious.

Of course, all bodies are abject, and that fact is what makes body horror such an attraction. From conception, our bodies enter a state of change that never ends, though we work to great lengths to create the illusion of static selves. Through the safety of either the screen, page, or canvas, we can explore those tactile and alien parts of our bodies in a way that is at least partially understood to be licit, and where we are encouraged to stare long and hard at the details rather than to turn away.

Some bodies are more attuned to change than others. Some bodies are marked.

For trans people in particular, there’s a draw to stories like Brundle’s, or like the ones you’ll find in fungal horror and fantasy works like Rivers Solomon’s Sorrowland, Aliya Whiteley’s The Beauty, and Jenny Hval’s Paradise Rot. In my academic double-life I contributed a book chapter to Bloomsbury’s forthcoming series on the cultural history of monsters that examines in particular the proliferation of fungal horror and its relationship to both environmentalism and the body. Intrinsic to that analysis was a recognition of the ways each of these novels and novellas uses the transformation brought about through fungal infection or awakening to explore both queer and abject forms of sexuality and gender performance. In Sorrowland, queer Black desire and radical self-love are coupled with its protagonist’s acceptance of her ever-mutating body, while in The Beauty, mating with Whiteley’s seductive, post-apocalyptic fungus women results in male impregnation and the transformation of cis male bodies into more ambiguous ones.

Body horror is the genre of transformation and change.6

Whether transformation here is understood as loss or lack, as in the case of a body part severed and then focused on with particular and unusual intensity or manifested as the full-bodied mutation into a form we’d be hard-pressed to call human, these works each problematize the honesty and ubiquity of the normate body. Many trans people have an acute awareness of the body as something that’s always changing, even though this dynamic aspect of our natures is not exclusive to trans bodies, but universal. As abjected bodies, we also often experience ourselves as monstrous—as either amorphous or as excessive. While not all trans people experience dysphoria, it remains a common thread, and in body horror narratives, that experience is all but normalized as something one ought to feel when looking at the screen or reading a particularly evocative passage. We might not, in real life, perceive ourselves as desirable, but in body horror an unrelenting want oozes not merely from the screen, but from the audience. A deep, dark, terrible and wonderful part of us, aches to see Brundle’s “final” transformation and longs for the moment when the killer’s knife edges to the right and severs the threatened limb. We do this, even as we mourn, in many cases, for those characters.

There’s a tension here. A sense of disruption. It is, perhaps, uncomfortable to think of queer bodies (indeed, any bodies), in the way I’ve described here. Marginalized people, especially trans and disabled people, have an especially uneasy relationship with the abject. Nonetheless, there seems to me a radical fecundity in what body horror offers in terms of its appreciation of transformation and difference. The forms on screen challenge the impermeability of every body, revealing the uniqueness of our physical forms while dwelling in the uncomfortable knowledge of our own temporariness. Body horror rejects the rigidity of the classifications we like to naturalize: classifications that tell us there are such things as male and female or straight and gay in an essentialized and prescriptive sense.

Body horror is both a challenge and a promise.

Footnotes

- I mean here not “right” and “left” as a political designation, but draw on the historical association of the left hand with Satan and perceived aberrance. ↩︎

- Brundle is not, in fact, on testosterone, though you’d be excused for relating to some of the transformations he endures. ↩︎

- Well, maybe in the case of Cats we can place it. ↩︎

- Julia Kristeva. The Powers of Horror: An Essay in Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia UP, 1982), 2. ↩︎

- The normate body, according to Disability Studies scholar Rosemarie Garland Thomson, is “the constructed identity of those who, by way of the bodily configurations and cultural capital they assume, can step into a position of authority and assume the power it grants them.” By “constructed,” what is meant is that the ideal of the normate body is not a natural bodily type, but one that is informed by historical, cultural, and social factors. In the case of twenty-first century America, this body (and its point-of-view) are understood as a social default, despite the fact that barely anyone can measure up to its highly specific standards. The normate is defined not only by what is is (e.g. white, middle class, male, Northern, able-bodied, Protestant, etc), but by what it is not. Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia UP, 1997), 8. ↩︎

- This is not to say that medical transition is a prerequisite for trans interest in this subgenre. Even as a young child, it was stories of people turning into things that fascinated me most: The Little Mermaid, stories of dragons shedding snakeskin to become human, tales of punishment coming in the form of curses that mutated or twisted the body. I suspect trans interest in body horror comes from the possibility, danger, and excitement of both the actuality of transformation and the simple idea of it. ↩︎

About Steve Hugh Westenra

Steve is a trans author of fantasy, science fiction, and horror (basically, if it’s weird he writes it).

He grew up on the eldritch shores of Newfoundland, Canada, and currently lives and works in (the slightly less eldritch) Montreal. He holds advanced degrees in Russian Literature, Medieval Studies, and Religious Studies. His current academic work focuses on marginalized reclamations of monstrous figures. He teaches the History of Satan and Religion and its Monsters.

In 2018, Steve’s lesbian Viking novel, Ash, Oak, and Thorn, was selected for the Pitch Wars mentoring program and agent showcase. During Pitch Wars, Steve was lucky to receive mentorship from fellow queer author, K. A. Doore.

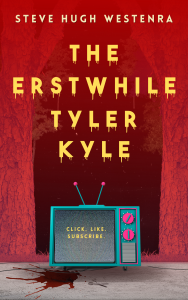

His queer horror comedy, The Erstwhile Tyler Kyle, was mentored by Mary Ann Marlowe in the inugural #Queerfest class.

He is a SPFBO9 entrant.

Steve is passionate about queer representation, Late Antiquity, and spiders.

Leave a comment